English translation of an interview with my father Günter Westphal by Friederike Gräff, originally published in taz newspaper on January 7, 2024 – with the addition of photos courtesy of Günter Westphal.

Original article: Künstler über Ästhetik als empowerment: „Auf Augenhöhe begegnen“

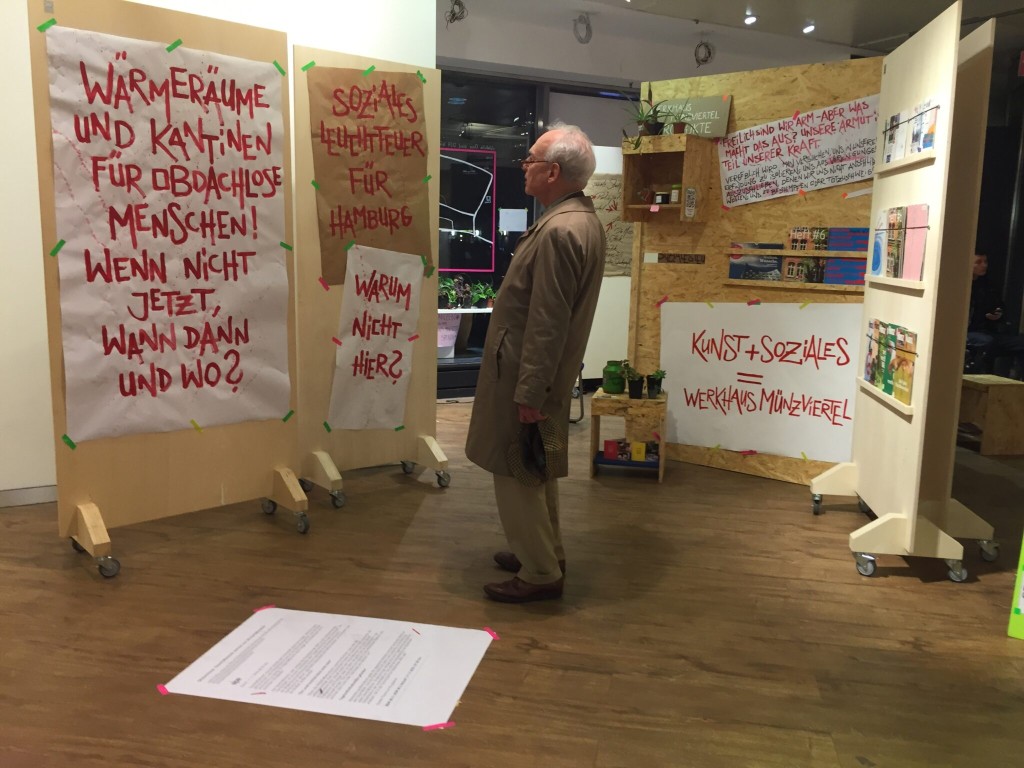

With the Werkhaus, the Hamburg artist Günter Westphal has created a place for young homeless people. A conversation about free time and self-discovery.

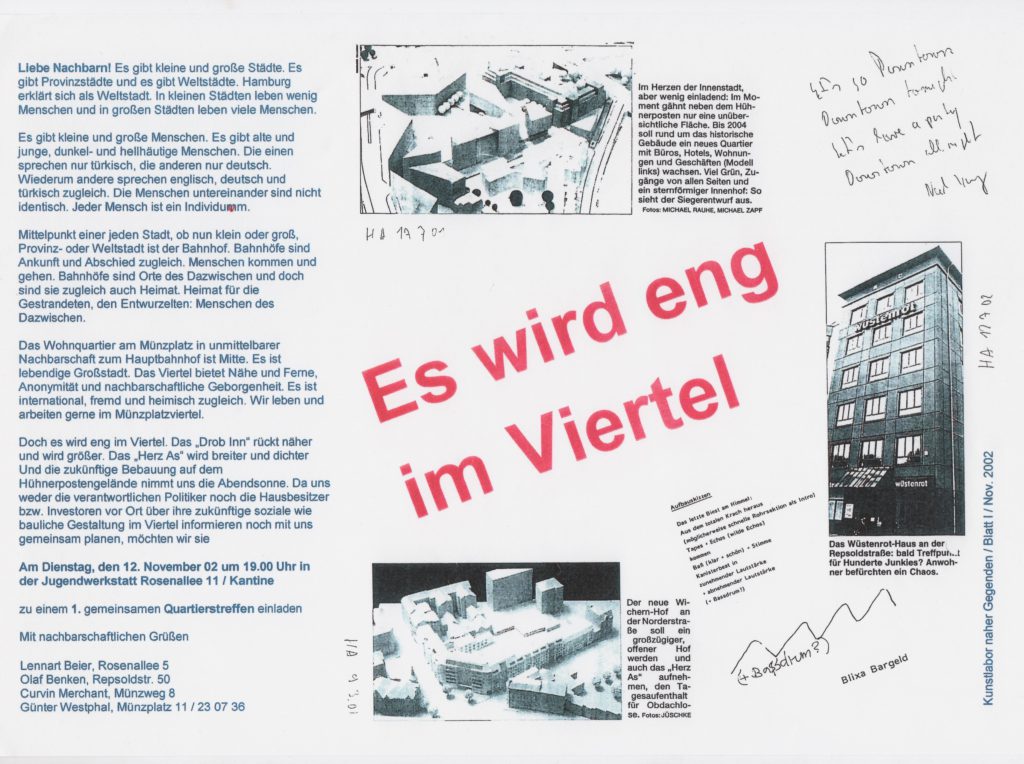

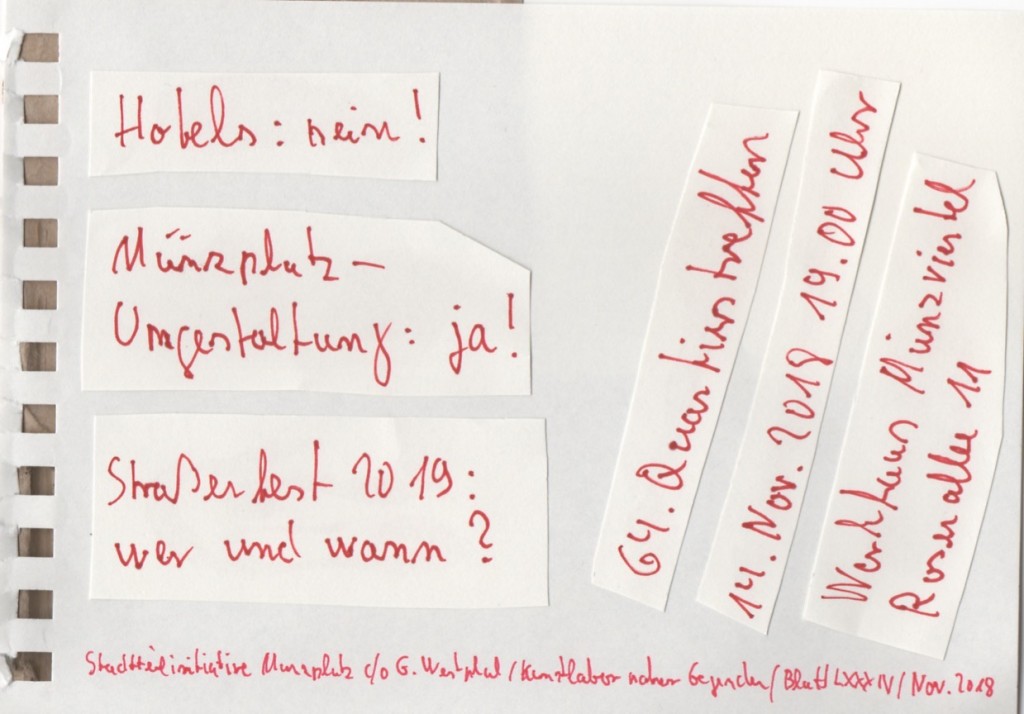

taz: You called the Hamburg Münzviertel a Gallic village. What’s Gallic about it, Mr. Westphal?

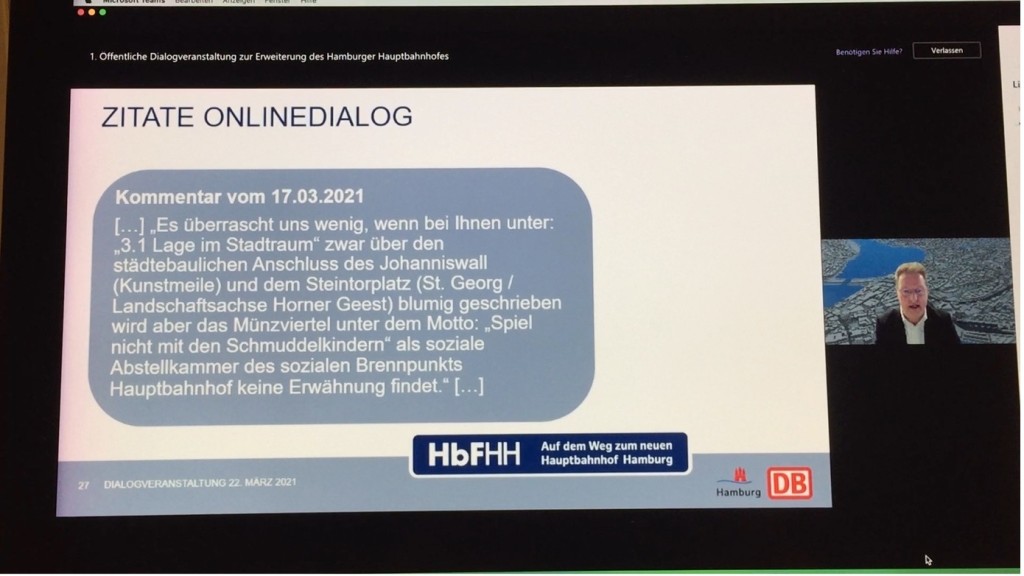

Günter Westphal: We are this small district south of the main train station that fights for participatory urban development. For me, participation means planning and designing for the common good at eye-level with everyone involved. Politicians and urban developers all have different expert knowledge, we have knowledge about neighborly coexistence – and that is equally important.

Who would you be in the Gallic village – Miraculix?

I hadn’t even thought about that… We are a community. I founded the district initiative with other Münzviertel residents 20 years ago, and 10 years ago the Werkhaus, a daytime center for young homeless people. And then purposely persevere with these activities. It is my elixir of life to bring artistic criteria with local people into urban planning.

What does it mean to “purposely persevere”?

When different people work together, you can be disappointed by the others because they don’t do something or don’t do it the way you thought it should be done. But I decided for myself to do this. So I am only responsible to myself and cannot demand responsibility from others.

What kind of people live in the Münzviertel?

Very different ones: students, homeless people and left-wing activists. Our characteristic feature is that we are at the back side of the main train station, we have a lot of social facilities here that you wouldn’t want to have on the other side of the train station. Then we have the Viertelzimmer [Quarter Room] and the “Münzgarden”, where we meet as neighbors. And for about ten years now, the district is being encroached by an excessive number of chunky new hotel buildings.

After ten years of Werkhaus: What succeeded and what failed?

Nothing failed at the Werkhaus. It is an identity-creating reflection of our community-oriented district activities. With the Werkhaus, we have created spaces in which we can meet the Werkhäusler [Werkhaus participants] at eye level.

What does that look like in practical terms?

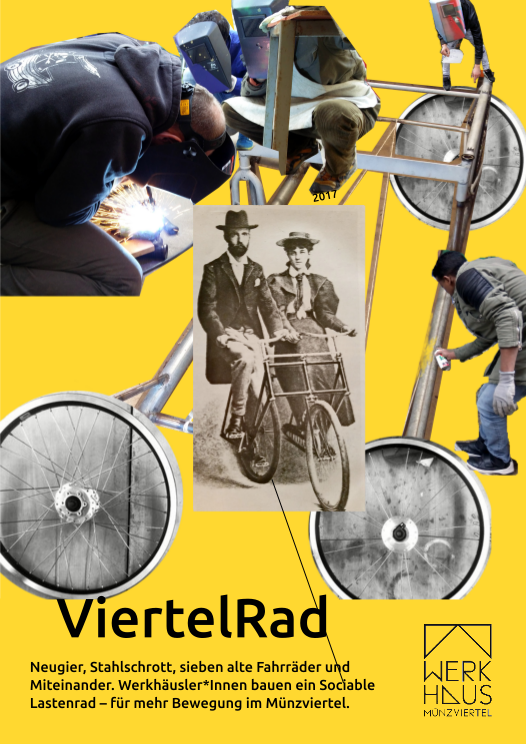

We have staff who, in addition to social-educational counseling, try to structure the day; shared breakfast and lunch – and there are artists who are here for six months and are trying out the interface of art and social issues. And we have workshops where the Werkhäusler can see whether they are good at working with wood or with bicycles or something else.

You once wrote: “It’s about resistance to the objectification of the individual by others.” Is this a language that reaches the participants?

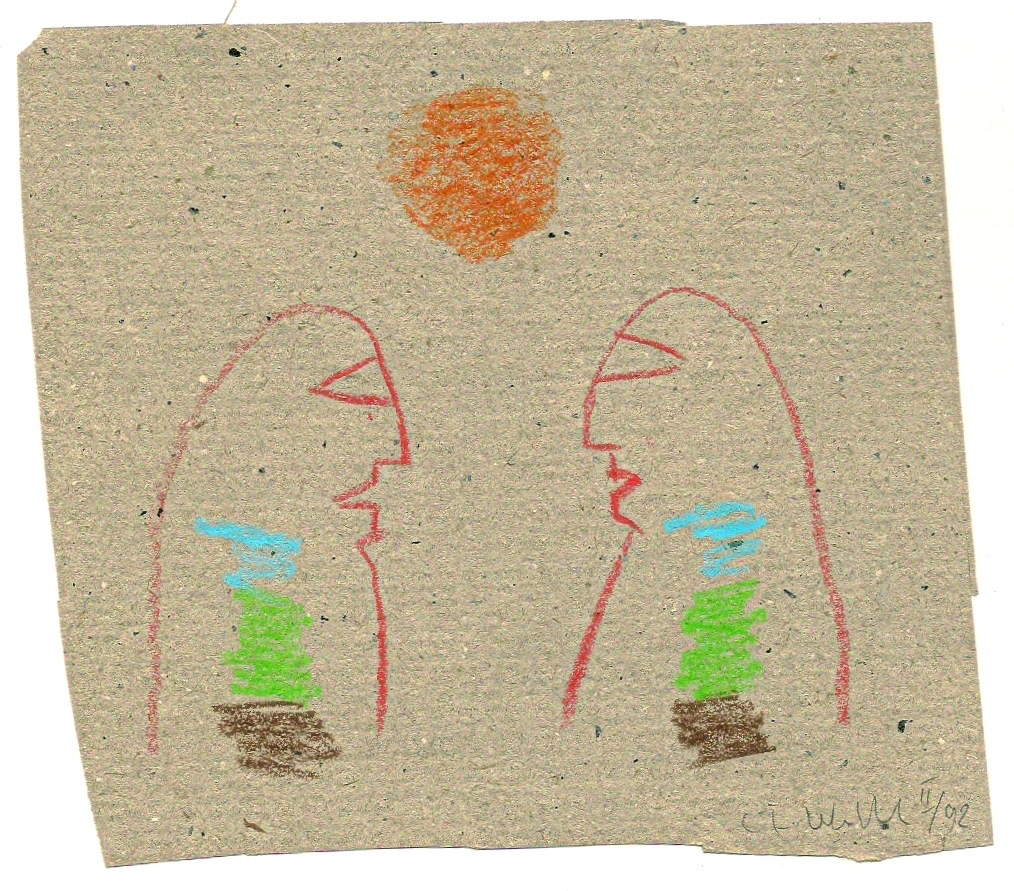

The Werkhäusler do not come here to become artists, but rather they are touched by art and perceive themselves as individual subjects. For every person, awareness of their own self, but participatorily also awareness of the other, only arises through sensuous experiencing, and through direct perception of the other – which is what I consider the “work field” of art.

Isn’t that a very idealistic concept?

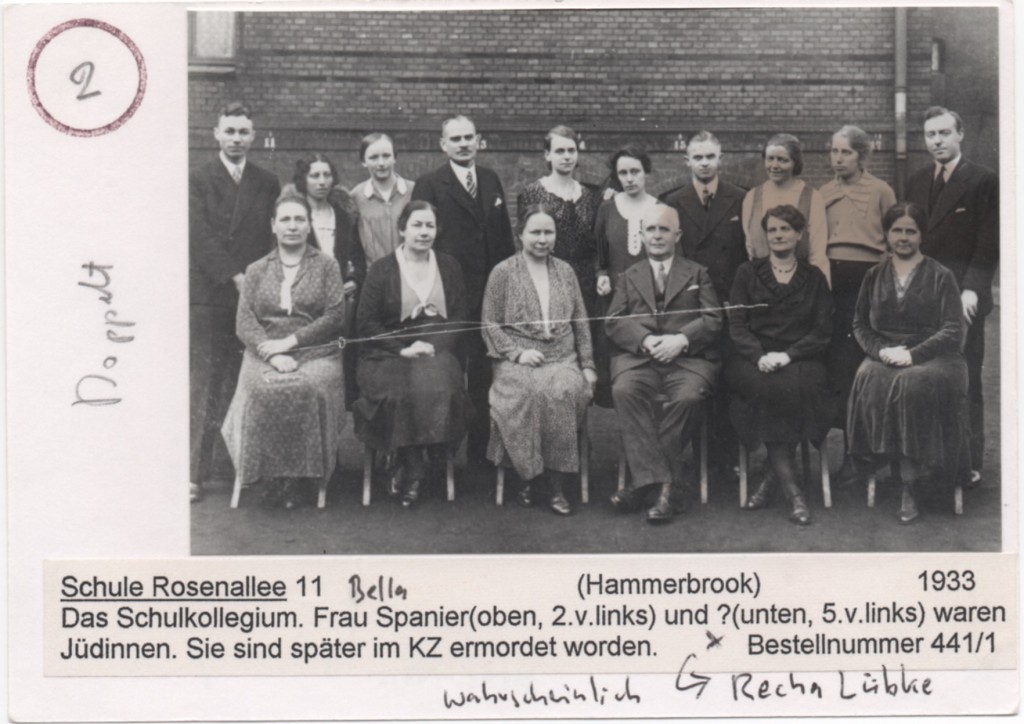

I am now 81, and I never believed that we would have to experience so many catastrophes again after the Nazi era. That’s why the large photo hangs there as a reminder…

It shows two Jewish teachers who taught at a school for girls in the same location where the Werkhaus is today. They were murdered by the Nazis.

They guard our actions.

What do you think it is about the aesthetics that counteracts this?

Aesthetics and ethics are like siblings.

Could you explain this connection again?

Let’s stick with the rose, even if that’s a cliché. It is a decision to judge whether it is beautiful or ugly. In the moment when I react to something and decide whether to be empathetic or dismissive, whether to preserve or exploit nature, then that is ethics. Then when I become active and create something like photographing or painting pictures, taking care of nature, I’m dealing with aesthetics. The first impulse to react and to decide always comes via sensuous experiencing and immediate perceiving.

When young people come here, do they feel that carpentry is preparing them for the future?

This is where things get a little complicated, we have a big content problem: the Werkhaeusler decide for themselves when they come to us and how long they stay. Because the main goal of the Werkhaus is to give the participants an unbound time, without an administratively prescribed time schedule, for their own self-discovery, perhaps for becoming a carpenter. We are financed by the social welfare authorities – they don’t have the term unbound time. There the question is whether someone is here for one, two hours, or days, which determines a different category of financing. That’s why I’m trying and hoping to achieve funding through the ministry of culture: for the human-related art concept of unbound time.

What are your experiences with the ministry of culture?

A year ago, I ran the “werkhaus 2.0” information kiosk with the Werkhaus in the old Karstadt Sports building as part of art in public spaces. As a follow-up, we tried to set up a Reallabor [living lab] “hostel for homeless people” there for 2024: a drop-in center for homeless people who could have showered in the basement and participated in the house. But it was rejected by them.

Who is “them”?

The creative society, which belongs to the ministry of culture. The desire for the homeless to disappear from the neighboring Mönckebergstrasse because they hurt business is deeply anchored in the creative society. Where we wanted to set up the Reallabor is now a coffee roasting company.

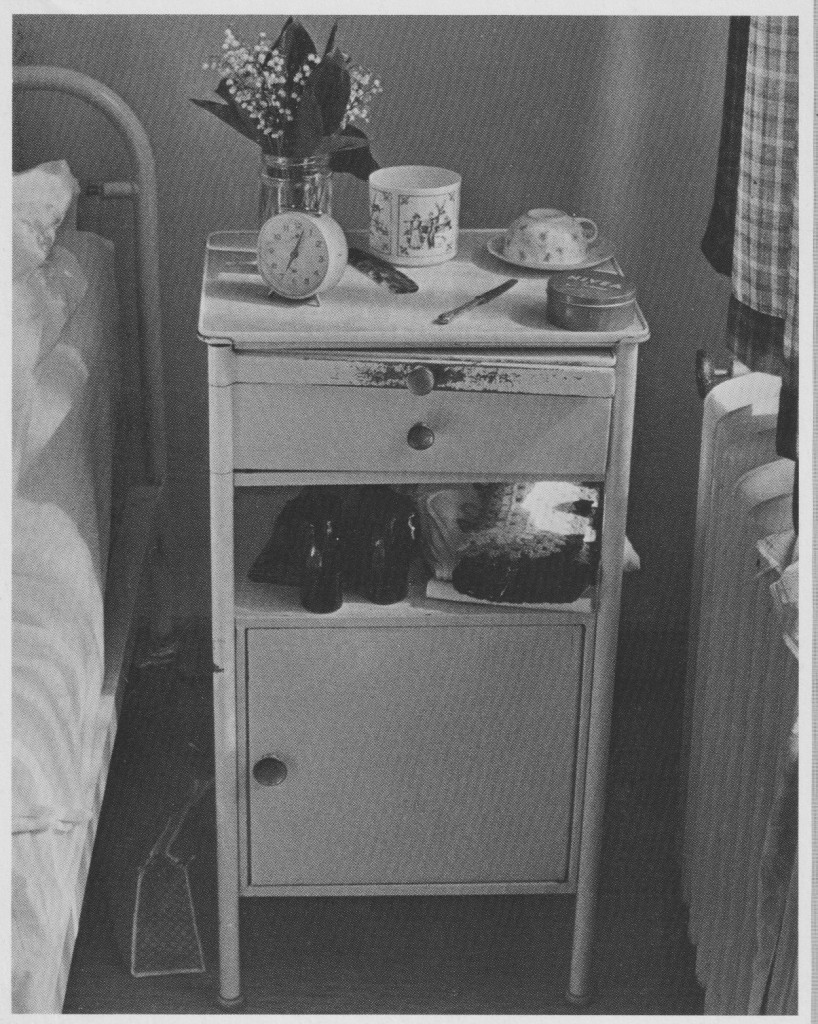

After studying art, you took the step into another world and worked in elderly care. How did that happen?

For me, as part of the “protesters of 1968”, it was a natural choice after college to go into the social sector, but always as an artist. I worked as an occupational therapist in a nursing home; it was the time when the home advisory councils were introduced. That interested me, and I worked there for almost ten years.

What were you able to do practically there?

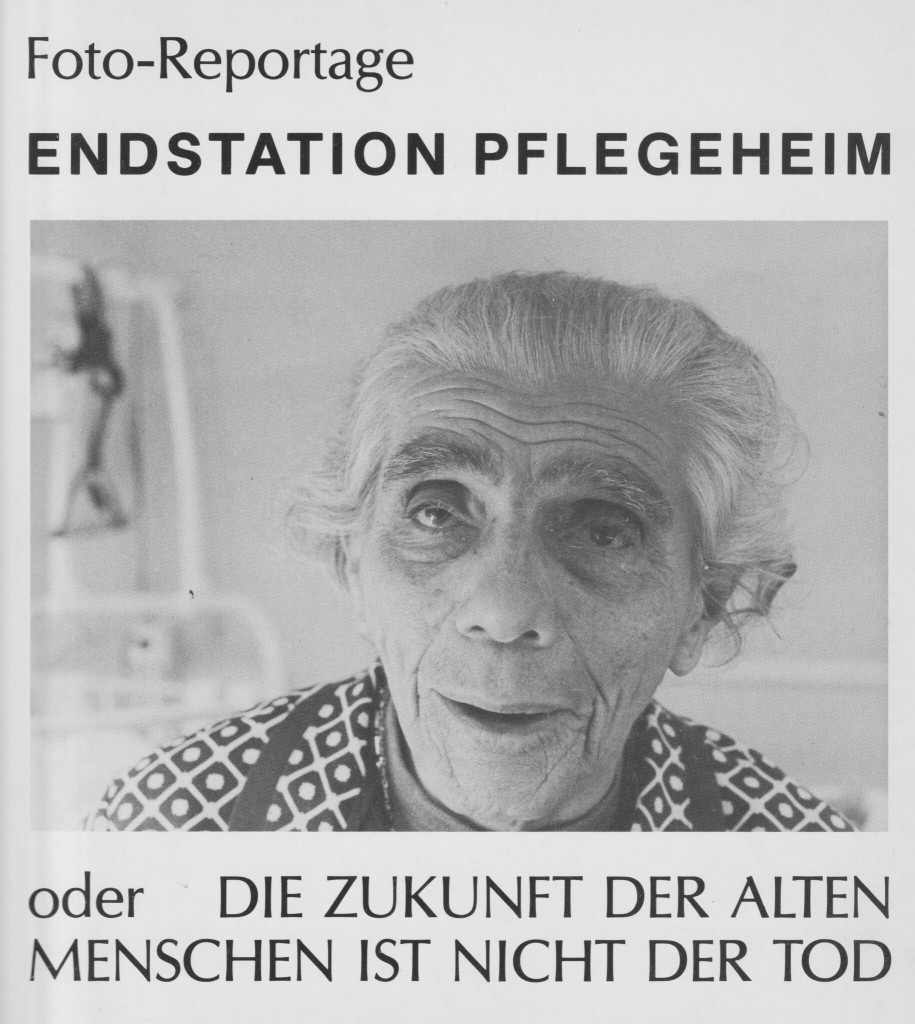

With the nursing home residents, I wove baskets, took photos together and went on excursions, always close with people. And I published a critical photo book about the nursing home and the home advisory councils, who acted as auxiliary police and given a cigar, coffee and cake and who were supposed to make sure that the other residents didn’t drink too much.

How close are photography and social work?

As a trained photographer, my aim is always to see, feel and woo the objects I want to photograph in order to present them in the best possible light.

You clearly differentiate your project from elite high culture – so clearly that one wonders where the depth of the antipathy comes from.

This is due to the economization of art and this very bourgeois understanding of art, where a museum is like a cathedral that, if possible, ordinary people are not allowed to enter. My art always sees itself as working with people.

I don’t imagine it’s easy as a founder to let all of this go at some point.

I’m in the situation now. At some point it’s the matter of the young and no longer mine. There are fantastic people who will continue this in their own way.

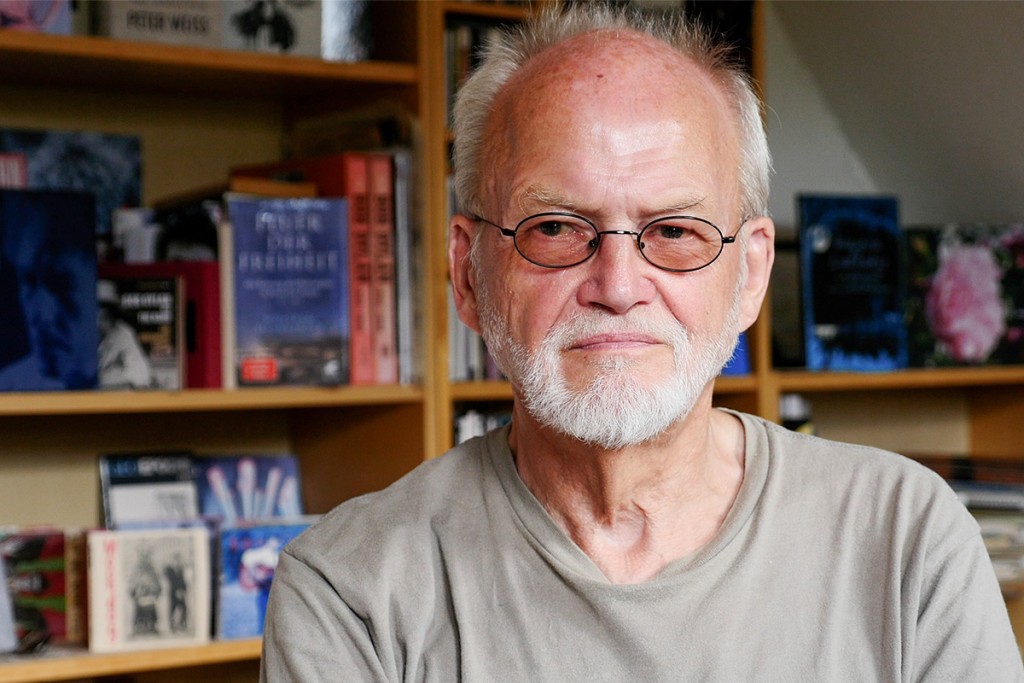

in the interview: Günter Westphal

81, trained photographer, studied at the HFBK Hamburg Kunsthochschule [Art Academy] from 1966 to 1972. From 1974 to 1979 he was a nursing assistant in a Hamburg retirement home.

In 2013, Westphal co-founded the “Werkhaus Münzviertel for interconnection of pedagogy, art and neighborhood work” in Hamburg: a low-threshold offer for unhoused and refugee young adults. It offers the opportunity to try out arts and craftsmanship and aims to combine pedagogy, art and neighborhood community work. There are also breakfast and shower facilities.

The Werkhaus is supported by the „Kunstlabor naher Gegenden“ [Art Laboratory of Nearby Areas] association and the non-profit organization “passage Hamburg”. Internet: https://werkhaus-muenzviertel.de